Energy Innovation partners with the independent nonprofit Aspen Global Change Institute (AGCI) to provide climate and energy research updates. The research synopsis below comes from AGCI’s Devan Crane, a Program Associate for Aspen Global Change Institute. A full list of AGCI’s updates is available online.

Peri-urban agriculture occurs where urban and rural land blend on a city’s fringe. Photo: Getty Images

Global supply chains are frequently disrupted by economic crises, wars, and political conflicts, but the COVID-19 pandemic caused a unique disruption felt by all. With the widespread damage to economies worldwide, food supply chains became stagnant, jeopardizing food security for many. Both urban agriculture and peri-urban agriculture, which takes place on the outskirts of cities, can contribute to regional food supply and shorten supply chains, enhancing both community control and resilience of food systems. But urban and peri-urban farmers face unique challenges in a rapidly urbanizing world. Emerging research sheds light on common challenges and solutions to preserving the resilience that urban agriculture affords our food systems.

What is urban and peri-urban agriculture?

Urban agriculture (UA) encompasses diverse practices within a city’s limits, from small apartment balcony gardens and raised grow beds in homeowners’ yards to neighborhood community gardens and walkable food forests to large-scale production plots and high-tech commercial rooftop gardens. Peri-urban agriculture (PUA) includes a similar diversity of practices, but occurs at the fringes of urban areas, where urban and rural lands blend. Peri-urban farms can be much larger than urban farms due to land use factors like zoning and land availability.

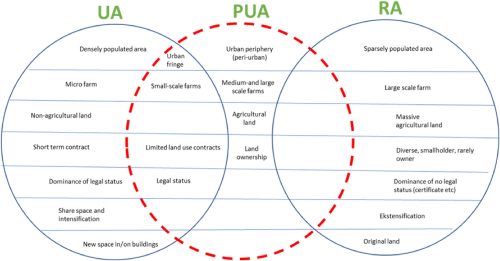

With rapid urban expansion, farms that were once rural can be enveloped by a city’s new development. Seventy percent of the global population is expected to live in cities by 2050 (Campbell et al. 2023), and the expansion of cities will continue to push agriculture into the periphery. As cities expand, farmers will have to adapt their farms to more urbanized land use policies and growing conditions (Figure 1) or be forced to relocate.

Figure 1. Characteristics of UA (urban agriculture), PUA (peri-urban agriculture), and RA (rural agriculture). “The attributes of rural and UA result in differences in their ability to meet the food requirements of urban populations. Urban agriculture can meet the same at the household level, while suburban agriculture can provide large quantities and has wide distribution channels. The different characteristics of RA, PUA, and UA create further challenges in dealing with situations according to local conditions and impact on agricultural planning and policy.” Source: Mulya et al. 2023, optimized from Opitz et al. 2016)

In a 2023 review of the benefits that peri-urban agriculture can provide to urban dwellers, also known as “ecosystem services,” Mulya and colleagues note that “many cities, especially those in developing nations, have limited access to fresh water, increased waste and sanitation problems, lack access to green spaces, and have declining public health.” Beyond offering urban residents opportunities to reconnect with nature and assert control over their food systems, urban and peri-urban agriculture can also help to mitigate some of the negative health and environmental impacts associated with urban development.

Both types of agriculture can offer many environmental and health benefits, including improving livelihoods and community connection, conserving wildlife habitats, promoting physical activity, and providing therapeutic relief. PUA and UA can also shorten food supply chains by reducing the distance between producers and consumers, and add value to waste through the use of local food scraps for on-farm compost or upcycled materials, like wood for raised beds. Well managed agricultural land has also been shown to improve soil, water, and air quality in surrounding areas, as healthy soil increases absorption area for runoff water and plants absorb CO2.

But farming in and near cities is not without its challenges. Urban land is typically heavily polluted from vehicle outputs, road runoff, artificial light, and human-made noise. Moreover, urban land is scarce and in high demand, making it expensive, and it is often not permitted for agricultural activities.

“Necessity is the mother of invention”

A report from CGIAR Initiative on Resilient Cities showcases several examples of how peri-urban and urban agriculture have improved food system resilience in communities of Sri Lanka and Ukraine during times of instability. The report explores recent efforts to increase food system resilience, comparing them to past efforts.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in the 1990s, for example, Cuba no longer received subsidized fuel and agricultural products from the USSR and faced a restrictive trade embargo from the US. These changes caused a sixty percent decline in available food for the people of Cuba. In response, Cuba’s national agricultural program directed municipalities and organizations to cultivate all unused land with intensive organic agriculture. While the effort was not enough to feed all of Cuba’s population, it greatly reduced food unavailability. It was an impressive development from Cuba’s national agricultural program, which was essentially non-existent before the collapse and is now a full-force production system of over 300,000 urban farms and gardens that produce about fifty percent of the island’s fresh produce.

Man tends an organopónico – a government-subsidized system of urban and peri-urban farming – in a suburb of Havana, Cuba, 2012. Photo: Mark Thomas / Alamy

Sri Lanka experienced destabilized food security during the onset of the COVID pandemic, followed by a larger economic crisis that started in 2022. In response, the Colombo Municipal Council in Sri Lanka’s capital city called for the cultivation of food crops on 593 acres of public land within the city – and planted the lawn in front of Town Hall with crops. The Council developed a webpage to encourage schools and citizens to cultivate every inch of bare land, balconies, and rooftops. The central government even gave public servants Fridays off to grow crops, and the army was mobilized to produce organic fertilizer and cultivate state lands. As in Cuba, this was an impressive organizational effort for the Colombo Municipal Council, as there was no government department focused on urban agriculture before the pandemic.

Urban agriculture has become a new necessity for Ukraine’s urban residents as well. Russia’s invasion of the country collapsed supply chains and caused food price shocks around the world. Vegetable prices have risen 85 to 150 percent, eggs have doubled in price, and Ukrainians now spend 70 percent of their income on food (compared to 23 percent before the war).

In response, public and private initiatives and support from the United Nations Development Program and Canada are scaling up urban farming efforts in many Ukrainian cities. These efforts are either entirely new or built upon existing campaigns, like the zero waste and organic food movements. One initiative offered free seeds to vulnerable populations to cultivate home and balcony gardens, similar to the victory gardens of World War One and World War Two. Additional support is also being provided by way of online education on urban farming.

Urban garden beside an apartment complex in a city center. Photo: iStock

What challenges do urban farmers face?

These examples can serve as a blueprint for policymakers and communities looking to bolster resilience in food systems that are increasingly susceptible to shocks from extreme climate disasters, natural hazards, geopolitical strife, and long-term climate impacts on agriculture. But scaling up urban and peri-urban agriculture will require overcoming some of the unique challenges these growers experience. In a recent article published in Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, Catherine Campbell and colleagues conducted a needs assessment of commercial-scale urban farmers in Florida.

Of the 29 urban farmers surveyed and interviewed by Campbell’s team, 90 percent owned or operated farms that had been in existence for 10 or fewer years, and 60 percent were in operation for five years or less. Eighty-three percent of their urban farms were five acres or less, while the average Florida farm is 246 acres (Census of Agriculture 2022). Vegetables were among their top three crops in gross sales, and a majority sold direct to consumers at farmers markets.

Farmers in the Campbell et al. study reported several advantages of farming in urban areas, such as providing opportunities for consumers to visit their farm and/or market stall, which can help to build deep relationships with their consumers.

Another benefit was the proximity of their farms to urban markets, which reduced travel time and cost associated with post-production transportation. Farming near large urban and peri-urban populations also made it easier for the farmers to find employees and volunteers to work on the farm.

But the study also surfaced common challenges facing urban and peri-urban farmers. Proximity to city dwellers was seen as a hindrance by some farmers. Curious neighbors can disrupt work or dislike the smells and noise that come with farm operations. Additionally, organic farmers need to know if their residential neighbors are spraying chemicals on their properties, as organic certifications often specify barrier lengths needed to protect crops from non-organic inputs.

Zoning and land-use regulations are another barrier farmers identified in both the Campbell and Mulya papers. Land use is often decided prior to land development, and city planners often don’t consider agriculture an urban activity. Conducting everyday farming activities, such as building a shed or driving a tractor, on land that is not specifically zoned for agriculture can require special fees and permits, adding time and expense to normal farm operations.

Furthermore, urban land is highly sought after by developers, as agricultural land is not valued as highly as residential land. Residentially or commercially zoned land is valued instead on its potential to be developed as a housing unit or a shopping center. Several farmers even reported being harassed by developers to sell their land for development.

Start-up capital is also limited for urban farmers. Most urban farms do not qualify for the same loans, grants, or subsidies that rural farms do, making up-front investments costly, regardless of farmers’ creditworthiness. This challenge is compounded when urban farmers don’t own their land, which was the case for over half those surveyed in Campell’s study. They have little control over future land use and are vulnerable to land use change, a barrier also mentioned by Mulya and colleagues.

How can we invest in urban and peri-urban agriculture?

Peri-urban and urban agriculture are by no means a cure-all, but they present significant opportunities to enhance food security, resilience, and sustainability in the face of global change.

When asked how barriers and challenges could be addressed, farmers mentioned that targeted government support, such as public assistance, education, grants, and subsidies would be helpful. Researchers also see a need for capacity building within governments to help maintain and develop peri-urban and urban agriculture areas and encourage policymakers to be strategic about how they think about land use change and land valuation (Mulya et al. 2023).

Whether the stresses stem from chronic urbanization pressures or acute shocks, researchers point to several avenues that can help build food system resilience:

- Government Leadership: Governments play a crucial role in promoting and supporting peri-urban and urban agriculture through policies, incentives, and initiatives that prioritize food security and sustainable urban development.

- Land Use Change Mitigation: Efforts should be made to mitigate land use changes that threaten peri-urban and urban farming, ensuring that agricultural land is protected and valued appropriately.

- Zoning: Revisiting zoning regulations to accommodate and encourage urban agriculture can help remove barriers and create a supportive environment for farmers.

- Subsidies, Grants, Financial Capital: Providing financial support, such as making subsidies and grants more inclusive, can help new and existing farmers overcome the high costs associated with urban farming, making it a more viable option.

- Education: Investing in educational programs and resources focused on urban farming can help build capacity, transfer knowledge, and support the growth of the sector.

- Valuation of other benefits: Recognizing and valuing the social, environmental, and therapeutic benefits of peri-urban and urban agriculture can help justify and prioritize its development.

- Further Research: Continued research is needed to better understand how peri-urban and urban agriculture can contribute to food systems, improve resilience, and enhance overall sustainability.

By addressing these areas, policymakers, stakeholders, and communities can promote and strengthen peri-urban and urban agriculture, creating more resilient and sustainable food systems for the future.

Featured Research:

Setyardi Pratika Mulya, S., Hidayat Putro, H. P., & Hudalah, D. 2023. Review of peri-urban agriculture as a regional ecosystem service. Geography and Sustainability, 4(3), 244-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2023.06.001.

Andrew Adam-Bradford, Pay Drechsel (2023). “Urban agriculture during economic crisis: Lessons from Cuba, Sri Lanka and Ukraine.” International Water Management Institute.https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7f14f676-0639-4314-8af6-a04549a3fa7a/content.

Campbell CG, DeLong AN, Diaz JM. Commercial urban agriculture in Florida: a qualitative needs assessment. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems. 2023;38:e4. doi:10.1017/S1742170522000370.