Energy Innovation partners with the independent nonprofit Aspen Global Change Institute (AGCI) to provide climate and energy research updates. The research synopsis below comes from AGCI Climate Social Scientist Rebecca Rasch. A full list of AGCI’s updates is available online.

In the year 2050, we may look back on the events of December 5, 2022, as game-changing for the clean energy landscape. This was the day that scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) produced using nuclear fusion technology. Unlike nuclear fission, which splits atoms to generate energy, nuclear fusion combines, or “fuses,” atoms to generate energy.

Fusion technology likely won’t be readily available for commercialization until mid-century, and even then, some argue it may prove too expensive to ever become commercially viable. Nevertheless, the milestone at LLNL is significant given the technology’s long-recognized potential. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency, fusion, the same process that powers the sun and other stars, could produce “four million times more energy than burning oil or coal” (Barbarino 2023).

Beyond the hurdles of technological readiness and financial viability, there is a looming question of whether fusion technology would face similar hurdles as nuclear fission technology in the court of public opinion given the tumultuous history of support for nuclear energy development in the United States (Gupta et al. 2019).

What is the state of public support for nuclear power and fusion energy?

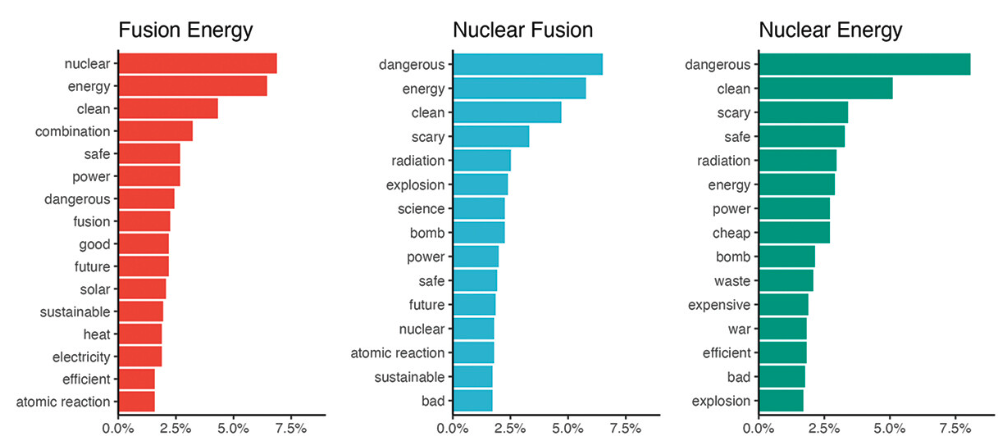

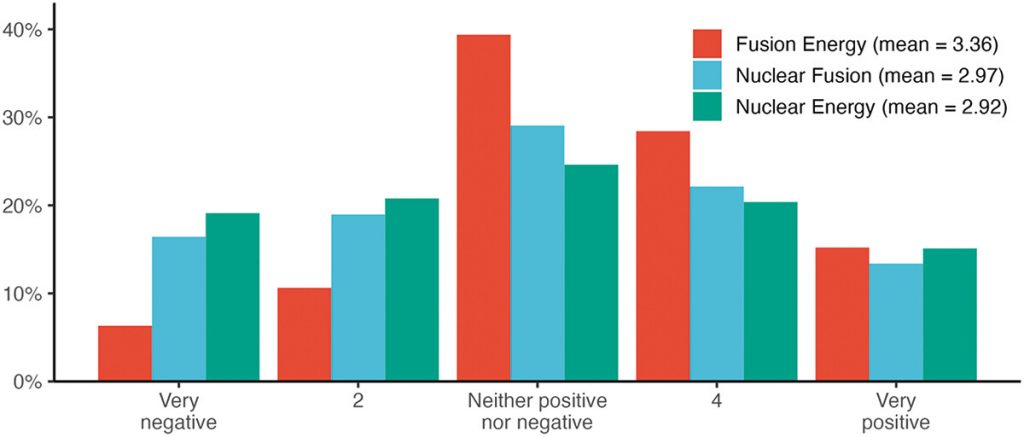

New social science research by Gupta and colleagues published in the journal Fusion Science and Technology utilizes a unique empirical lens to answer this question. The team surveyed a representative sample of U.S. households to understand current perceptions of and attitudes toward nuclear technologies, including feelings about the balance of risks and benefits, and support for or opposition to the construction of new nuclear energy power plants in the United States. They use an experimental design, randomly assigning respondents to reflect on three terms: “fusion energy,” “nuclear energy,” and “nuclear fusion.” While “fusion energy” and “nuclear fusion” are terms describing the same technology, “nuclear energy” refers to current nuclear fission technology.

By gathering public sentiment on each term, the researchers can distinguish how sentiment varies based on both the technology itself (i.e., fusion vs. fission energy technology) and feelings around the term “nuclear,” in general. The authors focus on understanding people’s emotional response by asking respondents to list three words or phrases that come to mind when they think about the given term (Figure 1). Next, they ask respondents how each word or phrase makes them feel, on a five-point scale ranging from very negative to very positive (Figure 2).

The most common terms people associated with “nuclear energy” were “dangerous,” “clean,” and “scary.” The mean response score to “nuclear energy” was 2.92 out of 5, where 3 is the midpoint, indicating neutral feelings. This result suggests that, on average, people tended to attach neutral or even slightly negative feelings to the term “nuclear.” Similarly, the most common terms associated with “nuclear fusion” were “dangerous,” “energy,” and “clean.”

The mean favorability score for “nuclear fusion” was 2.97, only slightly higher than the score for “nuclear energy.” Conversely, “fusion energy” tended to evoke more positive feelings, with a mean response score of 3.36. The terms associated with “fusion energy” were more benign, with only 2.5 percent associating fusion energy with “dangerous.”

The authors highlight the clear bias that respondents tended to hold against the term “nuclear,” especially given their lack of familiarity with fusion energy. According to this research, more than half of Americans (63 percent of respondents) are not familiar with fusion energy technology. Yet once presented with the concept of fusion energy, 58 percent of respondents said they would support the “construction and use of fusion reactors to generate electricity in the United States.” This is in contrast to the amount of support for current nuclear fission technology, which only 48 percent of those surveyed support. The researchers find that support for construction of fusion reactors is higher among those aged 18 to 34, those more familiar with the technology, and those concerned about the environment.

This generational difference in support for fusion energy is not surprising, considering the history of public support for nuclear energy development in the U.S. In the 1970s and 1980s, public support for nuclear power was significantly eroded due to accidents related to nuclear waste disposal and explosions at nuclear fission facilities, most notably the Three Mile Island nuclear plant explosion in Pennsylvania in 1979 (Gupta et al. 2019). A new generation has come of age since that time, and Gupta et al. (2024) find that those born in the 1990s and later are less likely to attach negative feelings to or oppose nuclear energy.

What drives public sentiment around nuclear power in the United States?

In a separate study published in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Kwon and colleagues (2024) at the University of Michigan used large language models (LLMs) to classify the sentiment of approximately 1.26 million English-language nuclear power-related tweets posted from 2008 through 2023. The LLMs categorized both key themes of the tweets as well as which tweets were most associated with positive, neutral, and negative sentiment. This novel approach allowed the authors to go beyond simply identifying sentiment to provide visibility into the drivers of those emotions.

The authors chose to use Twitter/X as a data source for public sentiment over alternatives like Instagram, Facebook, or LinkedIn for several reasons, including “the platform’s concise text format and its widespread use for discussing both scientific and non-scientific topics.” The team further segmented the data by city and state for 300,000 of the 400,000 tweets originating in the U.S. to understand geographic variance in support for nuclear power.

The authors found that nuclear power-related tweets tended to fall into two distinct categories: those pertaining to nuclear energy and those pertaining to nuclear policy. Nuclear energy-related tweets referenced nuclear power generation and related processes (including nuclear waste). Below are examples of tweets that typify negative, positive, and neutral nuclear energy tweets, respectively.

- “Nuclear power generates dangerous radioactive wastes, and the U.S. should stay away from this energy source.’’

- “The U.S. should build more small modular reactors to ensure a clean energy transition.’’

- “There are 440 nuclear power plants operating in the world.’’

Tweets classified as nuclear policy referred to geopolitics, world leaders, and/or nuclear weapons. Words and phrases in tweets classified as policy tweets included references to nuclear warheads, nuclear deal, North Korea, Iran, Benjamin Netanyahu, and Hillary Clinton.

The researchers utilized GPT-3.5 to determine that a majority of tweets (68 percent) were policy-related, and 26 percent were energy-related (Figure 3). Favorability sentiment varied considerably by topic, with most policy-related tweets classified as negative and energy-related tweets as mainly neutral. Where energy-related posts were not neutral, there was a roughly even split between positive and negative sentiments associated with energy tweets, with slightly more positive tweets. This suggests that the bulk of negative-sentiment tweets related to nuclear power is associated with geopolitical concerns, not energy development.

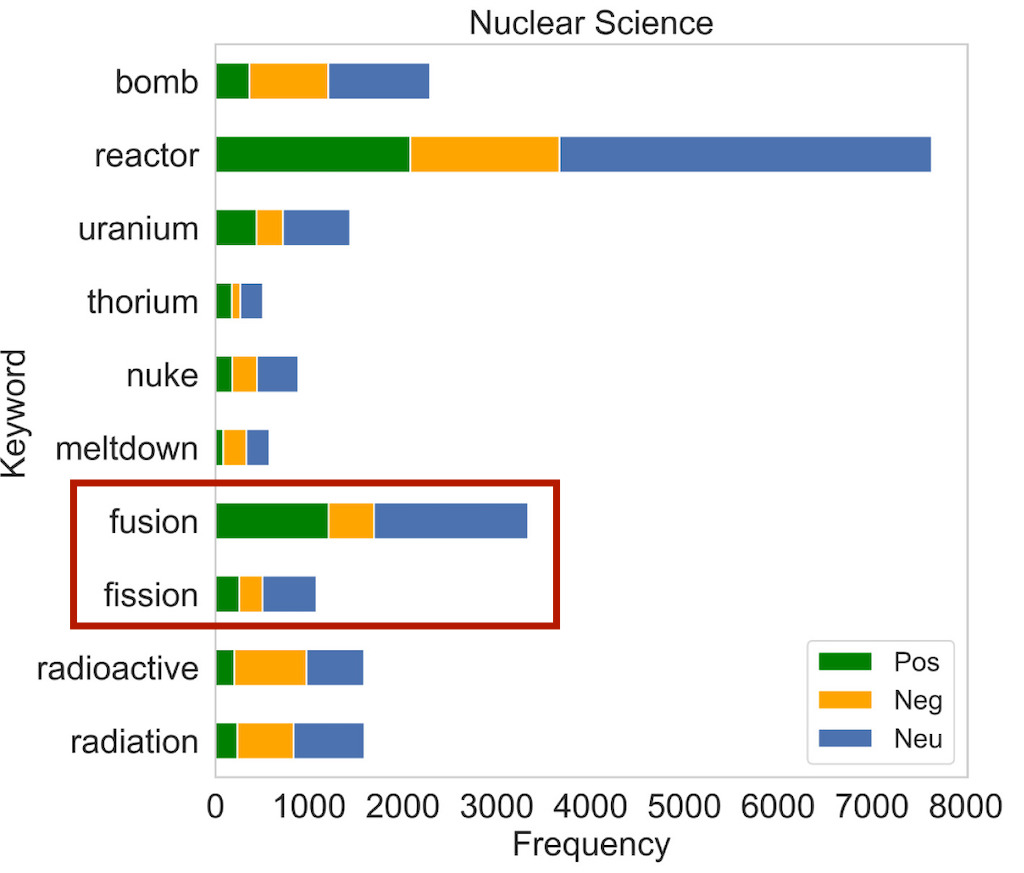

To understand the themes driving the sentiments associated with energy-related tweets, the authors used LLM topic models to identify frequent keywords. Based on keyword frequencies, the authors grouped tweets into six main themes: Nuclear Science, Other Energy Sources, Environment and Health, Nuclear Technology, Errors and Misuse, and General.

The authors grouped tweets that mention “fusion” and “fission” into the Nuclear Science theme. Figure 4 shows the distribution of sentiments of energy-related tweets by keyword for the Nuclear Science theme. The bulk of positive tweets in this theme contain the keywords fusion or reactor, suggesting fusion technology is partially responsible for the positive-sentiment tweets associated with nuclear energy-related tweets overall. Additionally, tweets in the Nuclear Technology theme skewed positive, further suggesting that advances in technology are driving positive sentiment tweets.

Interestingly, the distribution of sentiments of tweets mentioning fusion and fission aligns well with Gupta and colleagues’ (2024) survey results, which show similar distributions of sentiments for fusion and nuclear (i.e., fission) energy (see Figure 2). Both studies show a majority of neutral or positive sentiment for fusion, and a larger proportion of negative sentiment for fission, compared to fusion.

Concern for the environment is driving public support for nuclear power

Tweets grouped into the Environment and Health theme and that contain the keywords clean and renewable also skew positive, suggesting that positive-sentiment tweets around nuclear power are also driven by concern for the environment and an interest in clean energy development. This finding aligns well with Gupta and colleagues’ (2024) finding that those concerned about the environment are more likely to support nuclear energy development.

The notion that nuclear power is more appealing to those concerned about the environment is a distinct shift in public motivation for nuclear power generation, which historically was driven by industrialists interested in lower energy costs. This suggests an evolution of environmental concern in the past decade, where climate change mitigation efforts are taking precedence over more traditional environmental interests of biodiversity loss, environmental contamination, and degradation.

In a recent perspective piece for WIREs Energy and Environment, “Nuclear power and environmental injustice,” Höffken and Ramana (2024) argue that nuclear power is wholly incompatible with environmental justice, pointing to a legacy of nuclear reactor siting and waste disposal in socially marginalized communities. Fusion energy, which theoretically would not produce the type of radioactive waste that the fission process generates (as it does not rely on uranium or plutonium), could help address this perception of incompatibility. As fusion technology advances, it will be important to include the environmental justice community in planning and implementation to ensure transparency, procedural justice, and a more equitable distribution of environmental benefits, risks, and impacts than we have seen historically with nuclear energy development.

LLM-based analysis tracks with survey data, demonstrating the power of AI to categorize sentiment

Gupta et al. (2024) and Kwon et al. (2024) both focus on understanding U.S. public sentiment around nuclear power. Although their methods for gathering public sentiment differ substantially, their findings converge. Based on both a representative sample of the American public and 300,000 U.S.-based tweets, the research suggests a lack of majority opposition to nuclear power, in general, and fusion technology, in particular. In the case of fusion energy, the data indicate a slight majority of support.