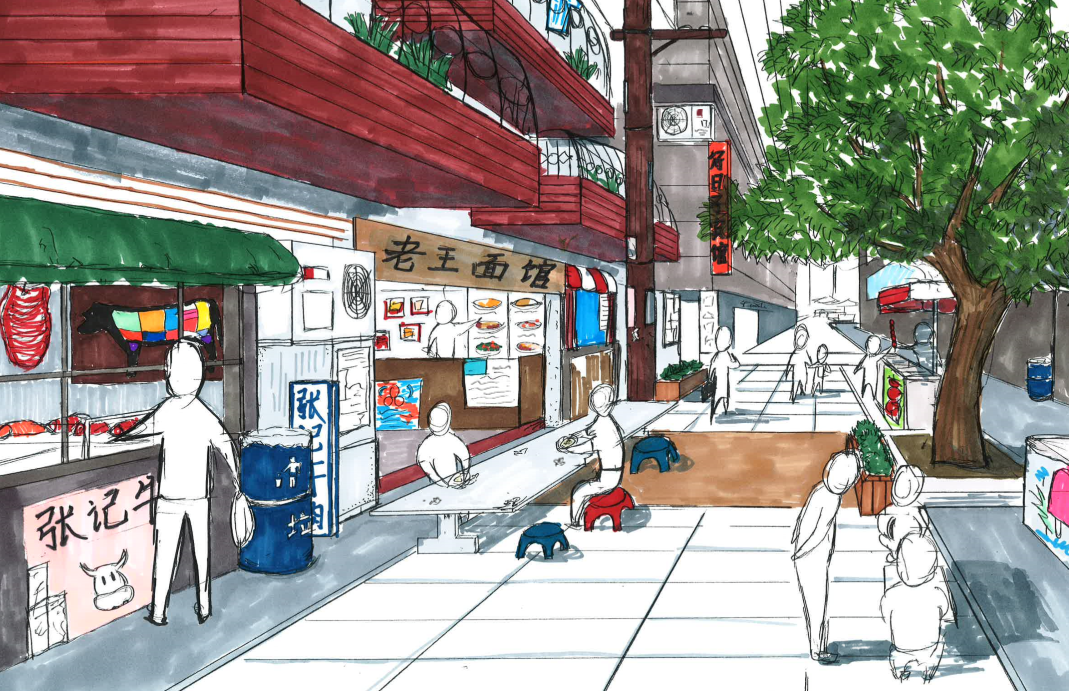

Active frontage, trees, comfortable sidewalk space, and mixed-use contribute to a great walking experience. (Artwork by Boshi Fu for Energy Innovation).

Last month, China’s State Council released urbanization guidelines to strengthen the management of urban planning and construction. Caijing magazine’s Xuan Zuo asked Energy Innovation CEO Hal Harvey for his thoughts on these guidelines and the future of China’s cities. The full interview is here. Harvey founded Energy Foundation, ClimateWorks, and most recently Energy Innovation, all with the goal of accelerating the transition to a clean energy economy.

Energy Innovation, in partnership with Energy Foundation China, has recently released its own set of guidelines to inform sustainable urban planning. The contents of these guidelines, China Development Bank Capital’s Green and Smart Urban Development Guidelines, closely mirror those released by China’s State Council. In general, the emerging consensus around sustainable urban development principles demonstrate a strong move in the right direction for China’s urbanization efforts. Below are some highlights from Caijing’s interview with Harvey.

On what defines a great city:

“When defining a great city, I think the most important factor is whether it is ‘people-centered’.” This means incorporating urban elements that focus on people, not the car, the street, or the building. There are handful of great cities around the world, including in China, that include people-friendly features such as small blocks and narrow streets, mixed-use development, public transit, non-motorized transit, and more. As more of China’s population moves into cities, which will likely increase their density, establishing these types of features will be key to maintaining quality-of-life.

Growth in many American and European cities has leveled off, while China’s cities continue to swell. That’s not to say these cities do not have the opportunity to continue enhancing and updating their urban features over time. Harvey emphasizes, “when there is a [time for a] change, the most important thing is to make it in the right direction.” Existing systems need not be torn down completely, but they can be improved at the natural rate of their infrastructure lifetimes. This means retrofitting old buildings with more energy-efficient designs, or when a dilapidated road needs updating, re-designate it as transit-only or add a bike lane.

On cars and traffic:

Currently, only one-tenth of China’s population owns a vehicle. But despite this low rate, roads across China’s cities are crippled by congestion, and these idling cars are a major contribution to air pollution. “Some policymakers still believe that to solve city traffic jams, they should increase roadways.” Harvey argues that expanding roads to hold more cars actually has the opposite effect by encouraging more drivers. He point out that in the U.S., for example, the most congested cities also have the highest highway miles per capita. “The most important thing is whether you allow cars to control the city or people to control the city.”

In meeting people’s “mobility” needs:

“Today, people think that private cars equal mobility.” Harvey notes two problems to this. First, too many cars on the road eliminate the ability for other modes of transportation like walking. Second, people have begun to think of travel—rather than arrival—as the end purpose. “Small, integrated communities with bike lanes and sidewalks allow people to quickly and easily arrive at their destinations.”

Improving public transit is another efficient way to provide mobility options to residents. “Many Chinese bus lines run slow and contribute to traffic congestion, so people do not arrive to their destinations on time. But if you build high-quality BRT (bus rapid transit)… it would be a very good solution. Guangzhou has done this and had good results.” Harvey argues that roads should be viewed as a public resource and should be utilized to maximize mobility and transportation.

“Good transportation can be extremely cheap. A BRT route can be 2-3 percent the cost of building a subway. However, it requires political courage to accomplish. When you disallow cars from using certain lanes, people think it will increase traffic.” Harvey describes his experience with helping implement a BRT system in Mexico City, which “began as a nightmare.” However, he tells that as less road space was assigned to cars and more to public transit, people began to discover private driving was no longer the faster transportation option. They started transitioning from the private car to public transport once they made this realization.

On the importance of urban growth boundaries:

Urban growth boundaries are strongly emphasized in the State Council’s new guidelines. Harvey echoes the importance of this city feature, mentioning they “prevent sprawl and protect agricultural land, alleviate traffic problems, reduce air pollution and improve public transit usage.” Instead of expanding, Harvey argues that cities can do much work in re-vitalization and re-development.

The release of the new urban planning guidelines demonstrates monumental progress for China as it recognizes the social, environmental, and economic value of creating healthier, more vibrant, sustainable cities for its people.