Energy Innovation’s new report on California climate policy argues the state should adopt an ambitious 2030 target to reduce statewide greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to 40% below their 1990 level.

This strong yet achievable goal would get California halfway to its 2050 target in one-third of the time, and help the state maintain its clean energy leadership at a time of unprecedented global commitments to fight climate change.

In light of recent climate science and new national commitments to cut emissions, we show why 40% is needed to avoid dangerous warming and renew California’s leadership in advance of the December COP21 talks that will take place in Paris. We synthesize the latest California-specific research and show how it supports our recommendations.

In addition to recommending a 2030 target, the report also describes a method for how to get there. It proposes an extension of the state’s cap-and-trade program to provide an economy-wide ceiling (or cap) on emissions that declines over time. It generates revenue that can finance low-carbon investments in ways that reduce costs or ensure a fair transition. Finally, cap-and-trade introduces flexibility mechanisms that ensure costs remain manageable.

Beyond the use of cap-and-trade as a capstone policy, Energy Innovation recommends the continuation of a portfolio of sector-specific policies that would ensure steady reductions across a broad array of energy and technology categories. Our overview paper provides a summary of the priorities for sector-specific policies. A separate report provides detailed recommendations for policies targeting electricity supply and demand that would help to improve energy efficiency in existing buildings and increase the share of renewables in the electricity system.

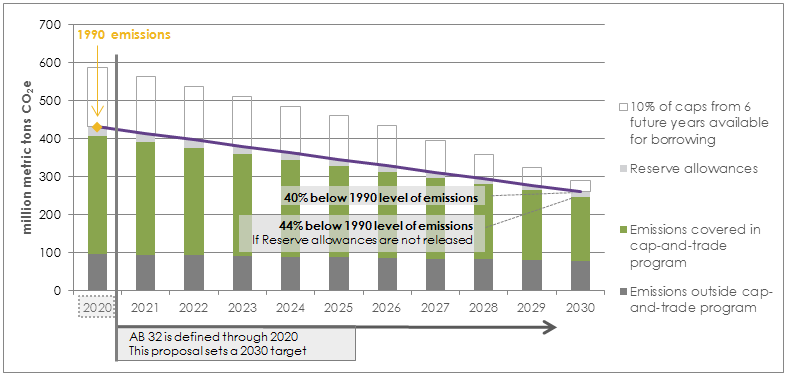

Proposed design for cap-and-trade’s continuation

Figure 1 shows how the proposed cap-and-trade program would help to put the state on a path to the recommended emissions target in 2030. Cap-and-trade drives down emissions by requiring those covered by the program to obtain “allowances” to emit GHGs, with every allowance representing one ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). (Offsets are an alternative compliance option that is discussed in the report.) The cap in any given year is equal to the total number of allowances that are made available.

The proposed design for the cap-and-trade program contains costs by setting aside allowances from the initial cap levels (for 2021 and into future years) at the outset of the program extension. If allowance prices rise to certain levels, the California Air Resources Board would make these “Reserve” allowances available at auction. Should this initial set-aside ever be depleted, allowances from future years could be accessed through a borrowing mechanism.

Figure 1 shows that if prices stay low and allowances from the Reserve are never tapped, statewide emissions would fall 44% below the 1990 level of emissions. If allowance prices rise high enough, released Reserve allowances would allow for higher emissions. Despite this potential for annual variation, cumulative emissions would still have a fixed limit equal to the sum of all the annual caps over the life of the extended program.

California in the larger climate context

As global carbon emissions have continued to rise, a sense of inertia has often paralyzed international negotiations. But all of that is changing thanks to two critical developments:

- There is increasing recognition among the public and policymakers that economic growth and carbon emissions can be decoupled. In California, since AB 32 passed in 2006, GHG emissions have declined by 6% (comparing 2007 emissions to the most recent data, 2012). Meanwhile, California’s economy has expanded by 9% over the same time period. In the past five years, OECD countries’ economies grew nearly 7% while their emissions fell 4%. Perhaps most impressively, last year, global emissions from energy use remained flat while economic output increased by 3%. One year doesn’t make a trend, but this is a hopeful development.

- The recent U.S.-China climate accord, which calls for the U.S. to reduce emissions 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025 and calls for China to peaking emissions on or around 2030, has completely changed the political and international environment. Previously, there seemed to be an unsolvable standoff between developed and developing countries. Today, countries are increasingly embarking on ambitious climate mitigation efforts, in large part because of the domestic benefits they will deliver. Dramatic cost improvements in clean technologies, the growing global market for these products, and increasing recognition of the health benefits are all driving the transformation.

- This is certainly true in China, which is trying to clean up its notorious air pollution. In its efforts to tackle smog, China is looking very closely at the California experience. Chinese officials want to know how policymakers greatly improved the air quality in Los Angeles, which had some of the world’s worst air pollution in the 1960s. California Governor Jerry Brown visited China in 2013 and the state has since stepped up technical cooperation with Chinese authorities.

Maintaining California’s climate leadership

It is no exaggeration to say that California deserves a slice of the credit for this moment of opportunity in efforts to solve the global climate crisis. In addition to its recent cooperation with China, the state’s outreach has extended to Mexico, Brazil, and Canada.

California is not alone in advancing clean energy in America—29 other states plus Washington, D.C. have also adopted mandatory renewable portfolio standards—and smart policies originating in California have often spread other states:

- California was the first to set building and appliance efficiency standards that are now widely used across the country and around the world.

- In 2002, California pushed forward with tailpipe greenhouse gas regulations, which eventually spurred the foundation of federal efforts to increase vehicle fuel economy.

- A policy analogous to state’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard has been adopted in Oregon, while states such as Washington are considering adopting similar policies.

To build on this momentum—within California’s borders, across the nation, and around the world—California needs to remain a clean energy leader. Governor Jerry Brown has set the right tone and outlined strong new goals in the realms of renewable electricity, building energy efficiency, and reducing dependency on oil for transportation.

One remaining, fundamental decision is what statewide cap on GHGs should be set for 2030. We believe 40% below 1990 levels would support the global push for 2030 commitments in the run up to Paris and allow California to continue reaping the many benefits of clean energy technologies.

Our proposal for reducing emissions 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 joins stringency and flexibility. It’s an ambitious goal, but it’s both achievable and economically sensible for California’s future.